Cleveland Volcano in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska photographed from the International Space Station

Cross-section through a stratovolcano (vertical scale is exaggerated):

1. Large magma chamber

2. Bedrock

3. Conduit (pipe)

4. Base

5. Sill

6. Dike

7. Layers of ash emitted by the volcano

8. Flank 9. Layers of lava emitted by the volcano

10. Throat

11. Parasitic cone

12. Lava flow

13. Vent

14. Crater

15. Ash cloud

A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in a planet's surface or crust, which allows

hot, molten rock, ash, and gases to escape from below the surface. Volcanic activity involving the extrusion of rock tends to form mountains or features like mountains over a period of time. The word volcano is derived from Italian vulcano, after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire.

Volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. A mid-oceanic ridge, for example the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has examples of volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has examples of volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates coming together. By contrast, volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the Earth's crust (called "non-hotspot intraplate

volcanism"), such as in the African Rift Valley, the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and the Rio Grande Rift in North America and the European Rhine Graben with its Eifel volcanoes.

Volcanoes can be caused by mantle plumes. These so-called hotspots, for example at Hawaii, can occur far from plate boundaries. Hotspot volcanoes are also found elsewhere in the solar system, especially on rocky planets and moons.

Volcanic features

The most common perception of a volcano is of a conical mountain, spewing lava and poisonous gases from a crater at its summit. This describes just one of many types of volcano, and the features of volcanoes are much more complicated. The structure and behavior of volcanoes depends on a number of factors. Some volcanoes have rugged peaks formed by lava domes rather than a summit crater, whereas others present landscape features such as massive plateaus. Vents that issue volcanic material (lava, which is what magma is called once it has escaped to the surface, and ash) and gases (mainly steam and magmatic gases) can be located anywhere on the landform. Many of these vents give rise to

smaller cones such as on a flank of Hawaii's Kīlauea.

Other types of volcano include cryovolcanoes (or ice volcanoes), particularly on

some moons of Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune; and mud volcanoes, which are formations often not associated with known magmatic activity. Active mud volcanoes tend to involve temperatures much lower than those of igneous volcanoes, except when a mud volcano is actually a vent of an igneous volcano.

Skjaldbreiður, a shield volcano whose name means "broad shield"

Fissure vents

Main article: fissure vent

Volcanic fissure vents are flat, linear cracks through which lava emerges.

Shield volcanoes

Main article: shield volcano

Shield volcanoes, so named for their broad, shield-like profiles, are formed by the eruption of low-viscosity lava that can flow a great distance from a vent, but

not generally explode catastrophically. Since low-viscosity magma is typically low in silica, shield volcanoes are more common in oceanic than continental settings. The Hawaiian volcanic chain is a series of shield cones, and they are common in Iceland, as well.

Lava domes

Main article: lava dome

Lava domes are built by slow eruptions of highly viscous lavas. They are sometimes formed within the crater of a previous volcanic eruption (as in Mount Saint Helens), but can also form independently, as in the case of Lassen Peak. Like stratovolcanoes, they can produce violent, explosive eruptions, but their lavas generally do not flow far from the originating vent.

Cryptodomes

Cryptodomes are formed when viscous lava forces its way up and causes a bulge. The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was an example. Lava was under great pressure and forced a bulge in the mountain, which was unstable and slid down the North side.

Volcanic cones (cinder cones)

Holocene cinder cone volcano on State Highway 18 near Veyo, Utah.

Main articles: volcanic cone and cinder cone Volcanic cones or cinder cones result from eruptions that erupt mostly small pieces of scoria and pyroclastics (both resemble cinders, hence the name of this volcano type) that build up around the vent. These can be relatively short-lived eruptions that produce a cone-shaped hill perhaps 30 to 400 meters high. Most cinder cones erupt only once. Cinder cones may form as flank vents on larger volcanoes, or occur on their own. Parícutin in Mexico and Sunset Crater in Arizona are examples of cinder cones.

In New Mexico, Caja del Rio is a volcanic field of over 60 cinder cones.

Mayon Volcano, a stratovolcano

Stratovolcanoes (composite volcanoes)

Main article: stratovolcano

Stratovolcanoes or composite volcanoes are tall conical mountains composed of lava flows and other ejecta in alternate layers, the strata that give rise to the name. Stratovolcanoes are also known as composite volcanoes, created from several structures during different kinds of eruptions. Strato/composite volcanoes are made of cinders, ash and lava. Cinders and ash pile on top of each other, lava flows on top of the ash, where it cools and hardens, and then the process begins again. Classic examples include Mt. Fuji in Japan, Mount Mayon in the Philippines, and Mount Vesuvius and Stromboli in Italy. In recorded history, explosive eruptions by stratovolcanoes have posed the greatest hazard to civilizations.

The Lake Toba volcano created a caldera 100 km long

Supervolcanoes

Main article: supervolcano

A supervolcano is a large volcano that usually has a large caldera and can potentially produce devastation on an enormous, sometimes continental, scale. Such eruptions would be able to cause severe cooling of global temperatures for many years afterwards because of the huge volumes of sulfur and ash erupted. They are the most dangerous type of volcano. Examples include Yellowstone Caldera in Yellowstone National Park and Valles Caldera in New Mexico (both western United States), Lake Taupo in New Zealand and Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia. Supervolcanoes are hard to identify centuries later, given the enormous areas they cover. Large igneous provinces are also considered supervolcanoes because of the vast amount of basalt lava erupted, but are non-explosive.

Pillow lava (NOAA)

Submarine volcanoes

Main article: submarine volcano

Submarine volcanoes are common features on the ocean floor. Some are active and, in shallow water, disclose their presence by blasting steam and rocky debris high above the surface of the sea. Many others lie at such great depths that the tremendous weight of the water above them prevents the explosive release of steam and gases, although they can be detected by hydrophones and discoloration of water because of volcanic gases. Pumice rafts may also appear. Even large submarine eruptions may not disturb the ocean surface. Because of the rapid cooling effect of water as compared to air, and increased buoyancy, submarine volcanoes often form rather steep pillars over their volcanic vents as compared to above-surface volcanoes. They may become so large that they break the ocean surface as new islands. Pillow lava is a common eruptive product of submarine volcanoes. Hydrothermal vents are common near these volcanoes, and some support peculiar ecosystems based on dissolved minerals.

Herðubreið, one of the tuyas in Iceland

Subglacial volcanoes

Main article: subglacial volcano

Subglacial volcanoes develop underneath icecaps. They are made up of flat lava flows atop extensive pillow lavas and palagonite. When the icecap melts, the lavas on the top collapse leaving a flat-topped mountain. Then, the pillow lavas also collapse, giving an angle of 37.5 degrees[citation needed]. These volcanoes are also called table mountains, tuyas or (uncommonly) mobergs. Very good examples of this type of volcano can be seen in Iceland, however, there are also tuyas in British Columbia. The origin of the term comes from Tuya Butte, which is one of the several tuyas in the area of the Tuya River and Tuya Range in northern British Columbia. Tuya Butte was the first such landform analyzed and so its name has entered the geological literature for this kind of volcanic formation. The Tuya Mountains Provincial Park was recently established to protect this unusual landscape, which lies north of Tuya Lake and south of the Jennings River near the boundary with the Yukon Territory.

Mud volcanoes

Main article: mud volcano

Mud volcanoes or mud domes are formations created by geo-excreted liquids and gases, although there are several different processes which may cause such activity. The largest structures are 10 kilometers in diameter and reach 700 meters high.

.jpg)

Erupted material

Lava composition

Pāhoehoe Lava flow at Hawaii (island). The picture shows few overflows of a main lava channel.

The Stromboli volcano off the coast of Sicily has erupted continuously for thousands of years, giving rise to the term strombolian eruption ejecting lava bombs

Another way of classifying volcanoes is by the composition of material erupted (lava), since this affects the shape of the volcano. Lava can be broadly classified into 4 different compositions (Cas & Wright, 1987):

If the erupted magma contains a high percentage (>63%) of silica, the lava is called felsic.

Felsic lavas (dacites or rhyolites) tend to be highly viscous (not very fluid) and are erupted as domes or short, stubby flows. Viscous lavas tend to form stratovolcanoes or lava domes. Lassen Peak in California is an example of a volcano formed from felsic lava and is actually a large lava dome.

Because siliceous magmas are so viscous, they tend to trap volatiles (gases) that are present, which cause the magma to erupt catastrophically, eventually forming stratovolcanoes. Pyroclastic flows (ignimbrites) are highly hazardous products of such volcanoes, since they are composed of molten volcanic ash too heavy to go up into the atmosphere, so they hug the volcano's slopes and travel far from their vents during large eruptions. Temperatures as high as 1,200 °C are

known to occur in pyroclastic flows, which will incinerate everything flammable in their path and thick layers of hot pyroclastic flow deposits can be laid down, often up to many meters thick. Alaska's Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, formed by the eruption of Novarupta near Katmai in 1912, is an example of a thick pyroclastic flow or ignimbrite deposit. Volcanic ash that is light enough to be erupted high into the Earth's atmosphere may travel many kilometres before it falls back to ground as a tuff.

If the erupted magma contains 52–63% silica, the lava is of intermediate composition.

These "andesitic" volcanoes generally only occur above subduction zones (e.g. Mount Merapi in Indonesia).

If the erupted magma contains <52%>45% silica, the lava is called mafic (because it contains higher percentages of magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe)) or basaltic. These lavas are usually much less viscous than rhyolitic lavas, depending on their eruption temperature; they also tend to be hotter than felsic lavas. Mafic lavas occur in a wide range of settings:

At mid-ocean ridges, where two oceanic plates are pulling apart, basaltic lava erupts as pillows to fill the gap;

Shield volcanoes (e.g. the Hawaiian Islands, including Mauna Loa and Kilauea), on both oceanic and continental crust;

As continental flood basalts.

Some erupted magmas contain <=45% silica and produce ultramafic lava. Ultramafic flows, also known as komatiites, are very rare; indeed, very few have been erupted at the

Earth's surface since the Proterozoic, when the planet's heat flow was higher.

They are (or were) the hottest lavas, and probably more fluid than common mafic lavas.

Lava texture

Two types of lava are named according to the surface texture: ʻAʻa (pronounced)

and pāhoehoe ([paːˈho.eˈho.e]), both words having Hawaiian origins. ʻAʻa is characterized by a rough, clinkery surface and is the typical texture of viscous lava flows. However, even basaltic or mafic flows can be erupted as ʻaʻa flows, particularly if the eruption rate is high and the slope is steep. Pāhoehoe is characterized by its smooth and often ropey or wrinkly surface and is generally formed from more fluid lava flows. Usually, only mafic flows will erupt as pāhoehoe, since they often erupt at higher temperatures or have the proper chemical make-up to allow them to flow with greater fluidity.Volcanic activity

A volcanic fissure and lava channel

Mount St. Helens in May 1980, shortly after the eruption of May 18

Shiprock, the erosional remnant of the throat of an extinct volcano.

Map of volcanoes

Active

A popular way of classifying magmatic volcanoes is by their frequency of eruption, with those that erupt regularly called active, those that have erupted

in historical times but are now quiet called dormant, and those that have not

erupted in historical times called extinct. However, these popular classifications—extinct in particular—are practically meaningless to scientists. They use classifications which refer to a particular volcano's formative and eruptive

processes and resulting shapes, which was explained above.

There is no real consensus among volcanologists on how to define an "active" volcano. The lifespan of a volcano can vary from months to several million years, making such a distinction sometimes meaningless when compared to the lifespans of humans or even civilizations. For example, many of Earth's

volcanoes have erupted dozens of times in the past few thousand years but are

not currently showing signs of eruption. Given the long lifespan of such volcanoes, they are very active. By human lifespans, however, they are not.

Scientists usually consider a volcano to be active if it is currently erupting or

showing signs of unrest, such as unusual earthquake activity or significant new

gas emissions. Many scientists also consider a volcano active if it has erupted in historic time. It is important to note that the span of recorded history differs from region to region; in the Mediterranean, recorded history reaches back more than 3,000 years but in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, it reaches back less than 300 years, and in Hawaii and New Zealand, only around 200 years. The Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program's definition of active is having erupted within the last 10,000 years.

Extinct volcanoes are those that scientists consider unlikely to erupt again, because the volcano no longer has a lava supply. Examples of extinct volcanoes are many volcanoes on the Hawaiian Islands in the U.S. (extinct because the

Hawaii hotspot is centered near the Big Island), and Paricutin, which is monogenetic. Otherwise, whether a volcano is truly extinct is often difficult to

determine. Since "supervolcano" calderas can have eruptive lifespans

sometimes measured in millions of years, a caldera that has not produced an eruption in tens of thousands of years is likely to be considered dormant instead of extinct. For example, the Yellowstone Caldera in Yellowstone National Park is at least 2 million years old and hasn't erupted violently for approximately 640,000 years, although there has been some minor activity relatively recently, with hydrothermal eruptions less than 10,000 years ago and lava flows about 70,000 years ago. For this reason, scientists do not consider the Yellowstone Caldera extinct. In fact, because the caldera has frequent earthquakes, a very active geothermal system (i.e. the entirety of the geothermal activity found in Yellowstone National Park), and rapid rates of ground uplift, many scientists

consider it to be an active volcano.

It is difficult to distinguish an extinct volcano from a dormant one. Volcanoes

are often considered to be extinct if there are no written records of its activity. Nevertheless volcanoes may remain dormant for a long period of time, and it is not uncommon for a so-called "extinct" volcano to erupt again. Vesuvius was thought to be extinct before its famous eruption of AD 79, which destroyed the towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii. More recently, the long-dormant Soufrière Hills volcano on the island of Montserrat was thought to be extinct before activity resumed in 1995. Another recent example is Fourpeaked Mountain in

Alaska, which prior to its eruption September 2006 had not erupted since before 8000 BCE and was long thought to be extinct.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

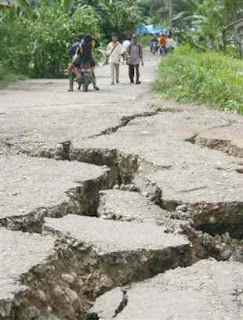

locked portion of the fault, releasing the stored energy. This energy is released as a combination of radiated elastic strain seismic waves, frictional heating of the fault surface, and cracking of the rock, thus causing an earthquake. This process of gradual build-up of strain and stress punctuated by occasional sudden earthquake failure is referred to as the Elastic-rebound theory. It is estimated that only 10 percent or less of an earthquake's total energy is radiated as seismic energy. Most of the earthquake's energy is used to power the earthquake fracture growth or is converted into heat

locked portion of the fault, releasing the stored energy. This energy is released as a combination of radiated elastic strain seismic waves, frictional heating of the fault surface, and cracking of the rock, thus causing an earthquake. This process of gradual build-up of strain and stress punctuated by occasional sudden earthquake failure is referred to as the Elastic-rebound theory. It is estimated that only 10 percent or less of an earthquake's total energy is radiated as seismic energy. Most of the earthquake's energy is used to power the earthquake fracture growth or is converted into heat